Kasheer: Musings from a Book Launch

4 minute read Retweet

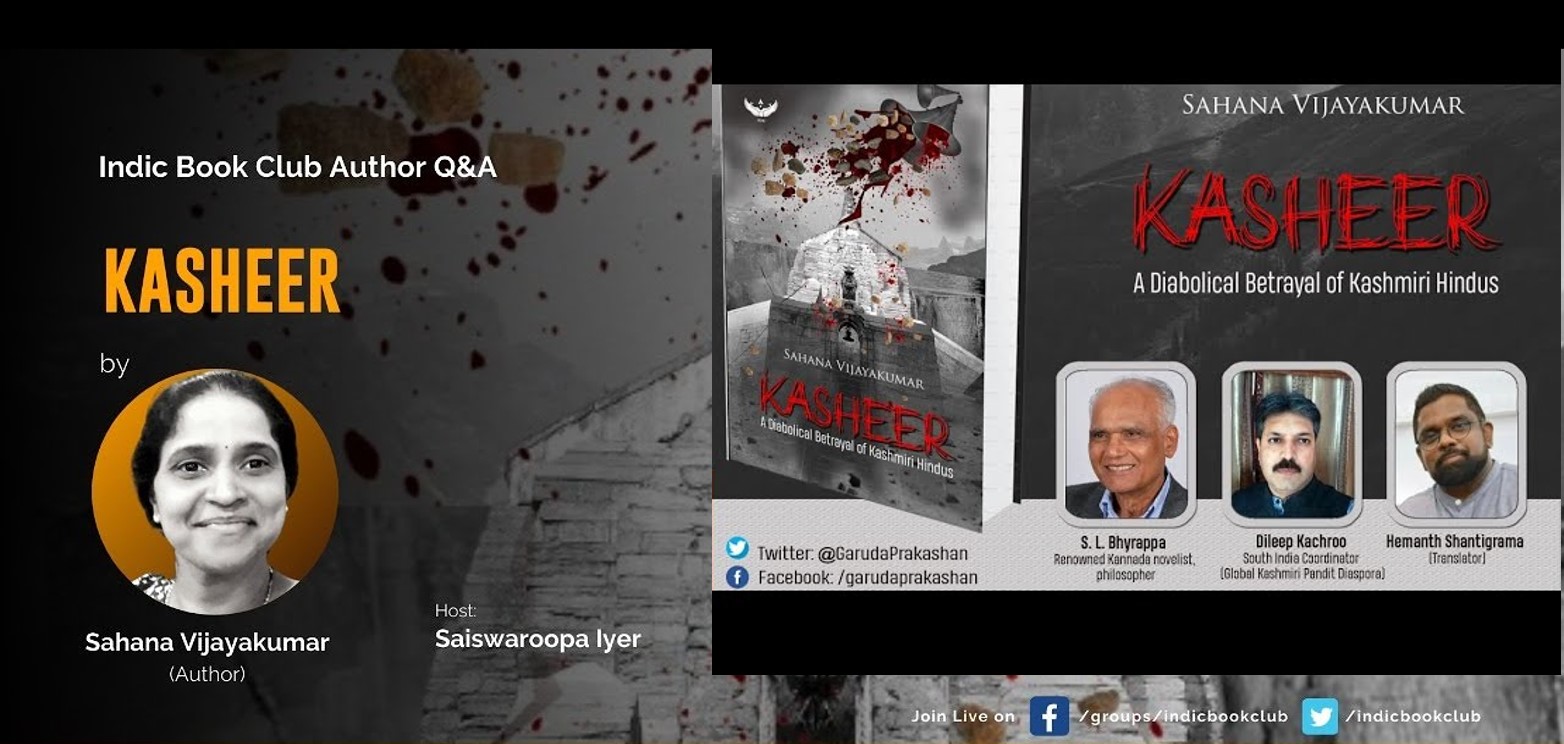

What follows are observations from two book launches (Garuda & IBC) of a well-received work in the genre of Indian historical fiction: Sahana Viajayakumar’s Kasheer.

When Shri S L Bhyrappa speaks, it is worthwhile to listen. During the Garuda session, he hypothesizes on the question that has grappled the Indian public and many historians for over 70 years: why did Sardar Patel willingly step away from being the first Prime Minister of India, when he was the overwhelmingly popular choice within the Congress party itself? There is no clear answer; we mainly know Gandhi asked him to, with various theories offered, including the unpopular Nehru’s international outlook and age in his favour. Here Bhyrappa posits that Patel would have been familiar with the way Gandhi’s machinations resulted in Bose resigning from the Congress Presidency a decade earlier. Perhaps Patel saw a similar fate awaiting him if he did not comply, instead choosing to sincerely carry out his duties to the nation without the top chair. Given Nehru’s immediate blunders on Kashmir, Gandhi’s diktat has left us with disastrous long-term consequences we have yet to resolve. Speaking on the horrific eviction of Kashmir Hindus in 1990, Bhyrappa asks: Will the kshatra virtue, our noble warrior spirit, breathe again?

When the internally displaced Kashmiri Hindu Dileep Kachroo asks 31 years later: “What stories can I tell my children?”, we know we have heard these cries before, over and over. Little has been done in a timely manner, and the return to homeland remains a complex issue, regardless of Article 370 being superseded, a move that Congress’ Rahul and Sonia Gandhi bitterly criticized. It is with sadness that Kachroo reminds us that even migrant workers during the COVID crisis were able to return home, but the Kashmiri Hindus cannot. The Western media has consistently chosen to portray the Kashmiri Muslims as not perpetrator but victim, with passing mention, if at all, of the Hindus they evicted, whose lands, property and culture they seized and eviscerated. As Sankrant Sanu notes: You cannot rob a people more than to prohibit their stories.

Twenty-five years ago, there would have been few outlets for a Kasheera or an Aavarana to be launched by the Anglicized global publishing houses. That trend has changed perhaps a little, but remains disproportionately left-liberal favouring Anglicized Indian writers of mediocre talent and high access. It is good to see a Garuda join the ranks of Voice of India, Sahitya Bhandara, and several others. The establishment and growth of indigenous-centred book forums like Indic Book Club (IBC) is also encouraging. As Sai Swaroopa Iyer of IBC points out when discussing the research involved in a subject as challenging as Kashmir, dishonesty can come into play when the book writing becomes more craft than art.

When one travels by air around the country, the selections on display in airport bookstores can make one cringe. Other than a few that have trickled through only in recent years, what is on offer is overwhelmingly written from an Indian outsider perspective, even if the authors appear Indian. Time will tell how much of the distribution challenge can be overcome, but it will be a long trial.

When translator Hemanth Shanthigrama talks about the challenges of staying true to the original Kannada of Kasheera (see review), we must not lose sight of the grander possibilities. While this drive for English-medium education continues to leave our native speaking children’s learning stunted, and with the still delayed opportunity to implement our base language Sanskrit, we must remember we are a country of multilinguals, a talent whose time has come.

Going further, the Indian diaspora has made its mark around the world, with expertise in a variety of foreign languages built over decades. Translating from Indian languages to English should be viewed as merely one step in the progression. The truer and more rigour-driven works must be offered in more of the world languages, including Spanish, Arabic, Russian, Mandarin, and in several other markets. Certainly, a keen audience awaits in Hungary, Poland and Japan, to name a few, that could benefit from at least one print run of a Kasheera or Aavarana and critical works in history writing in the foreign languages, ideally translated directly from Indian native tongues. This will require the continual encouragement of an active crew of international native-fluent translators who can enable a wider dispersion. We know our legacy colonial publishing houses won’t push for it: this is the opportunity. Furthermore, there is also brilliant publishing in foreign languages that will interest India’s readers in the various Indian languages. With time and a little vision, this revolution can come too.

Coming Soon:

Book Reviews of

Kasheer: A Diabolical Betrayal of Kashmiri Hindus, Sahana Vijayakumar, Garuda Prakashan, 2020

Kashmiri Pandits: Through Fire and Brimstone, Kashinath Pandit & Piaray Lal Koul Budgami, Akshaya Prakashan, 2020