Vishy Anand: Chess and India’s Forever Legend

Enough and more has been written about the impact of Viswanathan Anand, former multiple World Champion, the one-man revolution in Indian chess. As his 51st birthday approaches on 11 December, this is one fan’s thank you for what he has given to chess fans in India and around the world. We hope the non-chess player will see through some of the technical aspects offered below, and enjoy the story of Anand’s elevation, and the love that fans have for him around the world.

For much of the 20th century, especially since the 1930s, chess would remain the domain of the outstanding grandmasters of the former Soviet Union, who would hold a monopoly on who would even play for the world championship. Occasional genius from other shores would filter through and win, including the iconic American Bobby Fischer in 1972, but the line from Alekhine in the 1930s, to Kasparov and Kramnik into the modern era, would dominate.

The Soviets were well known to collaborate, keeping their systems of learning to their mutual benefit. It is under these conditions that a youngster from Chennai, with a propensity for speed play, entered the fray. Setting base in Spain with the kind assistance of a local family, he would slowly hone his skills on the European circuit, at the time when giants like Karprov and Kasparov were ruling. Anand was a promising talent of the 70s and early 80s, in an era where learning aids, beyond books and physically present coaches, were still in development. Thus, his rapid rise with all these impediments would be viewed as even more impressive.

Anand would enjoy success at major tournaments starting in the late 1980s, including Wjik an Zee, Linares, and later world championships in shorter formats. Other aspiring talents would also continually appear including Kramnik, Topalov, Ivanchuk, Leko, Polgar, etc. But a true chess champion has to be in the old tradition, the longer format classical in a one-on-one match against the reigning world champion, and not in a multi-player tournament. And somehow it would be Anand as the first of his exciting new generation of talents who would get a chance, at age 25, to battle for the world title against the indomitable Kasparov in 1995. 8 draws and then finally a surprising game 9 win for Anand would be met with a crushing rebuttal. Anand would be the third person that Kasparov successfully defended his title against.

The Longer Path

Anand would continue to win prestigious tournaments, but it would be Kramnik, who had earlier been Kasparov’s match assistant or “second” in 1995, who would shock Kasparov in their 2000 match, ending his 15-year reign at the top. Kasparov would retire from completive chess in 2005 at the age of 42. Kasparov of course was regarded by some as possibly the greatest in history till his time, and a pioneer in his own way. He was among the first to use computer aided chess databases, as well as focus on physical fitness that complemented his commanding over the board play. His analytical skills and ruthless objectivity in play were well known. His subsequent career as a public intellectual, if one is being ruthlessly objective, could be viewed as less than stellar, but that is another matter.

With various political intrigues within the chess world, it would be some time before the championship cycle could resume in a truly unified and undisputed manner, with a proper challenger cycle consistent with the past. Kramnik successfully defended his title against the Hungarian Peter Leko in 2004, but it would be two years later that the matters about disputed succession would be fully settled.

The very ascendancy of Veselin Topalov, with his high performance San Luis multi-player WC tournament win in 2005, signalled to many fans that Kramnik’s days were possibly numbered when they met in 2006. But Vladmir Kramnik played brilliantly to set aside the seemingly unstoppable rise of the Bulgarian, and confirm that he was indeed the rightful owner of the undisputed world classical chess championship since 2000.

Most fans around the world, and in India too where Volodya is very popular, were perhaps somewhat realistic and thus, not as optimistic about Anand’s chances when he finally got his crack at the title in Germany in 2008. Anand had earned his opportunity by winning the multi-player 2007 tournament in Mexico City.

A brief diversion first. In my own personal journey, and I say this with humour, the early childhood years were similar to Anand, in one aspect. My father taught me chess, while it was my mother who would keep playing with us children, well into the stage where we would pass her in abilities. Children love to learn and especially win, and grateful and lucky are those who have parents who enable it. By 2007, in my 30s, after years of self-study at an older age, I would play in two Karnataka state championships, finishing in the middle of the field, acknowledged by more advanced state and national players, as a respectable amateur. I had achieved one goal after years of diligence though: I was finally able to somewhat follow the games of the man who inspired me into years of self-study. Of course, I was always assisted by well-developed chess engines and the analytical capabilities of more advanced players I had befriended. But this learning is what kept my friends and I glued to various tournaments, including the ongoing championship cycles. Eagerly we watched the 2008 WC games live online, and hoped.

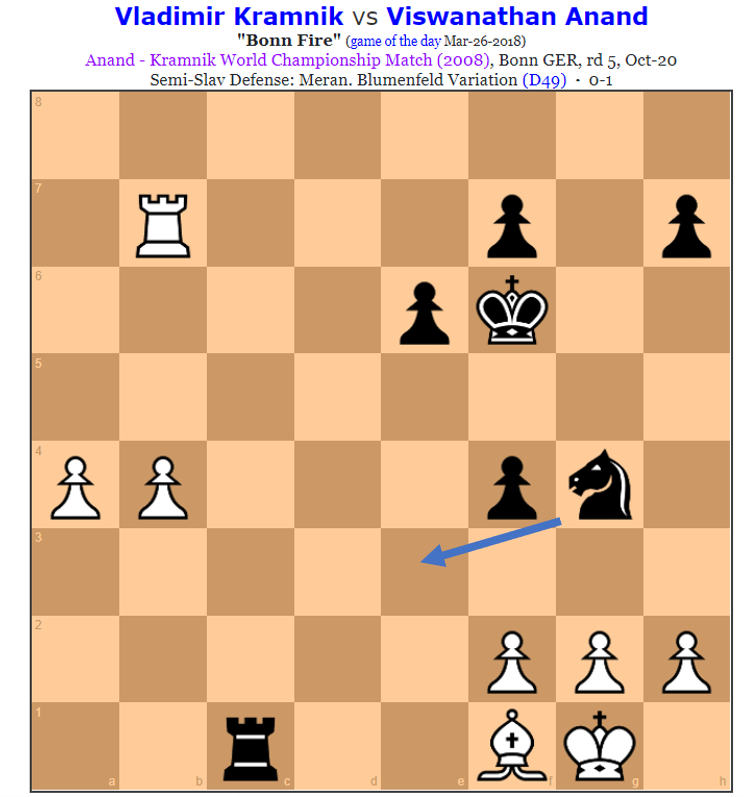

Anand Sets Bonn on Fire

Then it happened. The fire in Bonn, when Anand placed his Bishop on b2, in game 3. The chess commentators exploded with anticipation: Anand was going for it! Earlier he had deployed the all-important psychological trickery of deviating from his usual preferred “open game” first move of e4, something that he had largely stuck to his entire career. Instead, he would surprise his opponent and the world by deploying the less immediately tactical, the more “closed” d4 as his first move as white in game 2, that too in a world championship against no less an opponent than the great Russian. He won game 3, taking the lead in the 12-game match. In Game 5 again, Anand as black would again play Bishop to b2. In the earlier win, it might have been seen as a daring early move, offering possibilities to his opponent. But surely Kramnik was better prepared when Anand played an almost identical early move sequence in game 5?

In 2006, Kramnik’s battle with Topalov was mired in off the board psychological warfare, common at the highest level, where any edge was deployed to rattle the opponent. Here in game 5 against Anand two years later, Kramnik would find not only unexpected opening move choices, but also miss one of the more beautiful late game winning sequences in WC history. Anand would play 34…Knight to e3. One will need to be an advanced amateur at least, with plenty of assistance, to understand these specific descriptions of moves at the highest level, but suffice it to say, Anand had prepared a line with a spectacular final blow. Keep in mind, the rest of us are watching at home, aided by lively chess commentators like Peter Svidler, and chess engines, and praying that the sequence plays out. And it did. Kramnik had not seen through the depth of the calculation; even legends miss!

Imposing One’s Will

Chess is a game of imposing one’s preferred playing style on the opponent. To give a rough analogy from boxing, a Tyson style of boxer might prefer a shorter match with an early KO, while a Holyfield type of boxer will know his chances only improve as the rounds wear on, suffering early punishment, and then winning by wearing out the opponent. Chess theory has continually evolved, and while imposing one’s own preferred style of play is a big factor in winning, the greatest players are capable of playing in all styles, deemed “universal”, so that they are not caught unprepared, incapable of overcoming unusual variations. Kramnik as a positional genius is happier to slowly build his position till he overwhelms his opponent, while Anand is more known for his speed and willingness to right away engage in higher risk early hand-to-hand combat, with wild tactical possibilities that may even go against him. But both as universal players will play in any style when required.

The early psychological and risky gamble by Anand changing his opening choices was one thing. Now in game 6, Anand would go full Kramnik mode, playing in the preferred style of his opponent, and positionally outplay him! A 3-0 lead by game 6 (with the other 3 games being drawn) meant there was no looking back. Kramnik would manage to win one game later, but it would not matter.

For India, Finally!

The civilization that gave the world the gift of chess would now have its own world classical champion. The long line from the 1880s starting with the Austrian Willhelm Steinitz would now include Viswanathan Anand of India. The country exploded with joy, while the world applauded, for Anand and Kramnik had made this a most memorable encounter.

Personally, as an amateur fan, I could not believe what I was watching. I had the pleasure of meeting Anand and playing against him in a chess exhibition (“simultaneous”) in Chennai in 2006. As we had been told for too long, Anand was and remains one of the most popular and loved chess players of his era and of all time, known for his humility and approachability, a true ambassador of the sport.

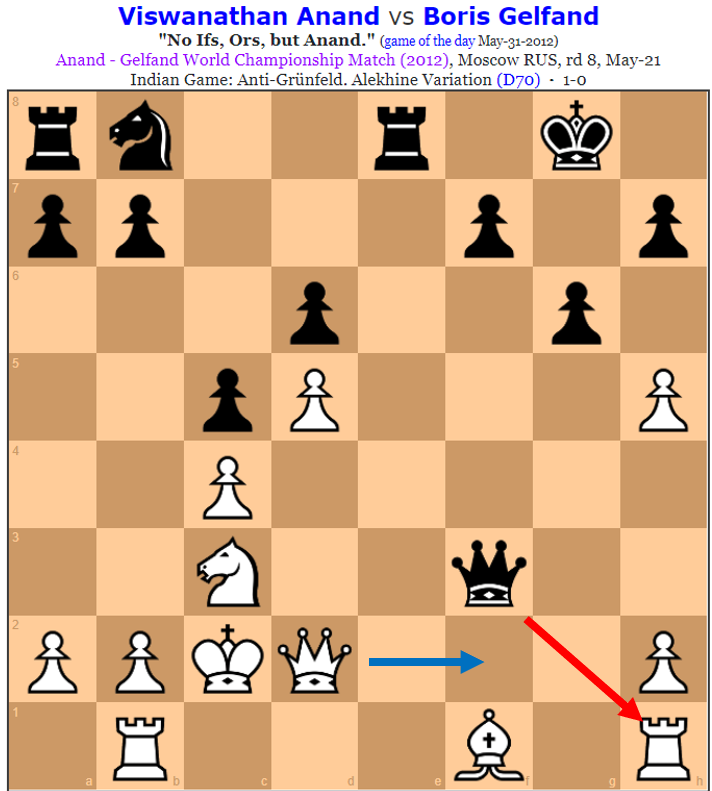

A defence of his title would follow, where he would daringly go play in Bulgaria on Topalov’s home turf in 2010, and retain his title. The Iceland volcano would play havoc in the late arriving Anand’s travel plans, making him lose his very first game, but he would show his mettle by immediately equalizing! Yet, as the match progressed, Anand would struggle to gain the initiative, even when having first move, prompting well-wisher Kramnik into joking in a later game, “Vishy, I see you have finally managed to equalize…with White.” But a final game error by Vesko meant Anand had conquered another formidable opponent, that too in his home. It may be of interest to remind fans that during this match, Anand received support from three world champions: Kasparov, Kramnik, and (future WC, and Anand’s “second”) Carlsen. Later in 2012, Anand would defend his title against the wily Boris Gelfand of Belarus, and again retain his title with one specific game, a tactically sharp 17 move win that reminded everyone of Anand’s usual brilliance and resilience, as a fond memory.

From a chess historian’s standpoint, in the post Kasparov era, one might say it is Anand that stands tallest among the vintage that followed Karpov and Kasparov. Not that it takes away anything from the fact that of all the people, it was the great Kramnik who replaced the seemingly invincible Kasparov as champion.

Father Time Never Loses

Chess knowledge is accretive, meaning with every passing decade, new ideas are brutally tested till they become part of the vast body of knowledge. This also means that a consistent top-10 chess player of the 21st century will have accumulated enough new techniques to contest favourably against past legends who did not have the easy access of modern databases, online reference material and high-performance chess engines that serve as idea generators and even as personal coaches. This has also helped increase the base of participation for determined (and often disruptively addicted) youngsters to become better players. The standards today have risen to such an extent that if you are not a chess grandmaster before your teens, you can forget about ever becoming World Champion.

Playing 7 hour chess games is akin to running a marathon, a physically grueling encounter, not just a psychological war. There are always highly energetic and determined youngsters in their 20s entering the fray, while it is common that by the early 40s, the energy levels dip. Rare are those who hold on as world champions in their 40s, as time catches up. Magnus Carlsen of Norway, a full 21 years younger, lived up to his own promise and earned his position at the top in a new era starting in 2013. Anand had laboured through almost three decades being a top player, and even had an unbroken run of being in the top 3 for a 12-year stretch, which itself would have been a remarkable achievement even if he had never hit the pinnacle. Yet he persisted.

Unlike lions that live together in a pride of mutual benefit, it is the bigger, stronger and faster tiger that works, at great risk, pulling down bigger prey, alone. Anand’s moniker, the Tiger of Chennai, is thus apt. He toiled against the giant lions of the Soviet school and other European countries, where facilities and economics were long to their advantage. And he hung on to cross the finish line, passing other legends who till this day acknowledge that Anand is very much a chess God. It is interesting to note that Kasparov’s reign ended when he was 37, while Anand’s only began at age 38. Such was the fire. And all along, he was among the most popular players among his own peers. As a fellow southerner, allow me to jovially say, it was all due to thayyir saadam, curd rice, one of our favourite comfort foods.

Images That Will Last Forever

We hope he will follow in the footsteps of other past greats and continue to enthral us in the later years, much like Victor Korchnoi, and add many more memories as an elder stateman of the game. His success and vast body of work has given us beautiful images, and may many amateurs continue to develop so that they can discover his magic for themselves.

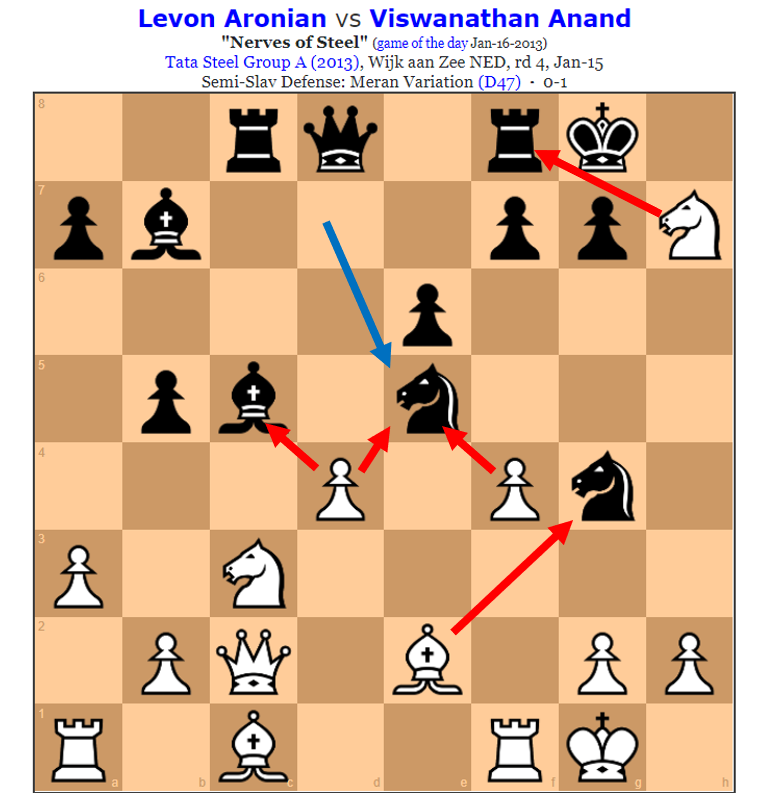

I will mention one other game, which by Anand’s own admission was one of his best, his magnificent one against the superb Armenian player, Levon Aronian, who himself was once seen as a possible future world champion. Imagine a tiger alone, facing 3 lions, and inviting a fourth lion to join the attack against him. In this 2013 game, Anand offers 4 options simultaneously: take any of my pieces, and no matter what, I will be ok. The complexity, the nerves, the beauty. Unbelievable. Levon perhaps may not ever get to the very pinnacle, but he too has been a pleasure to watch over his career.

This humble chess fan sends his early birthday greetings to arguably India’s greatest sports legend. Thank you Vishy for all the beautiful memories, and many more to come!

Coming soon: this Editor’s offers his humble suggestions on how much chess should your child play.

Image source: chessgames.com

Note: The word “wily” to describe Gelfand earlier is used in a positive sense only, as Boris is an extremely resourceful competitor, a hard player to beat. Peter Svidler is not only one of the most fun commentators to listen to, but a superb and popular player in his own right. (Shout out to Nigel Short, another past great who is a hilarious commentator as well)

Chess fans will also enjoy watching this 50th birthday compilation from a year ago.

Chess is a complex game just like life

AlphaZero is chess guru. 🐡 🐙🐳